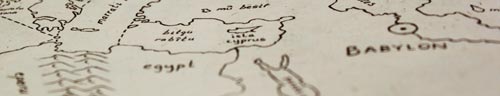

So, as promised, here is a little more info on one of my current projects. At its most basic, Translation is a map I've drawn incorporating an ancient Babylonian design, which I then tore into fragments, and distributed pieces individually to other artists. As the project is still 'live', some are currently working on 'restoring' or rebuilding different sections of this map, treating it as if it were an incomplete historical artefact. Because of this, I don't want to reveal too much of how my original looked, but I did want to show something of its style in these teasers.

The text below accompanied the exhibition COLONIZE at Third on Third Gallery, and gives the best attempt I've managed at explaining what it is I've set out to do with Translation.

The text below accompanied the exhibition COLONIZE at Third on Third Gallery, and gives the best attempt I've managed at explaining what it is I've set out to do with Translation.

In an ancient Babylonian artefact, the world is depicted as two concentric circles pressed into a clay tablet. Commonly known as the ‘Mappa Mundi’, it is only a couple of inches across, and outside the borders of the map is a dense covering of script, front and back. The inner circle represents the Earth, with Babylon at its centre. Surrounding this is a band of water, the ‘mê mūti’ or ‘bitter sea’, an ocean that extends to indefinable limits.

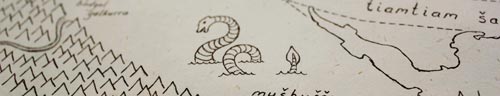

But somewhere out on the edges of this sea, on the map at least, are eight triangular outcroppings. These ‘nagû’ supposedly refer to distant lands rising out of the sea, yet they are not just physical outcroppings but linked inextricably to the culture and mythology of ancient Babylonia.

Each land is also a story, containing accounts of the fantastic creatures that can be found there or else a legend of an ancient king or battle, the Babylonian equivalent to filling in the empty areas of the map with images of fearful beasts and the warning: ‘here be dragons’.

No doubt these stories are based in truth somewhere, most likely accounts from travellers that have become distorted through their countless retellings and embellishments. Sadly, the words on the tablet have largely been lost, eroded over the years so that only fragments of text remain. And, in a different way, so have the blank spaces on the map. Satellite imagery has worn away the unknown corners of the globe and shows us the world as it is, not the world we imagined.

Yet any representation of the world transfixed onto a two dimensional surface comes with its own set of errors, distorting the earth’s contours to fit the shape of a square or rectangle. It is obvious in most commonly used maps today that Greenland and Antarctica look disproportionately huge, while the landmass of Africa is reduced to fit in place.

But somewhere out on the edges of this sea, on the map at least, are eight triangular outcroppings. These ‘nagû’ supposedly refer to distant lands rising out of the sea, yet they are not just physical outcroppings but linked inextricably to the culture and mythology of ancient Babylonia.

Each land is also a story, containing accounts of the fantastic creatures that can be found there or else a legend of an ancient king or battle, the Babylonian equivalent to filling in the empty areas of the map with images of fearful beasts and the warning: ‘here be dragons’.

No doubt these stories are based in truth somewhere, most likely accounts from travellers that have become distorted through their countless retellings and embellishments. Sadly, the words on the tablet have largely been lost, eroded over the years so that only fragments of text remain. And, in a different way, so have the blank spaces on the map. Satellite imagery has worn away the unknown corners of the globe and shows us the world as it is, not the world we imagined.

Yet any representation of the world transfixed onto a two dimensional surface comes with its own set of errors, distorting the earth’s contours to fit the shape of a square or rectangle. It is obvious in most commonly used maps today that Greenland and Antarctica look disproportionately huge, while the landmass of Africa is reduced to fit in place.

Can these modern and ancient styles of cartography be reconciled? The Babylonian view of the earth as a disk surrounded by sea, with Babylon, the modern day Middle-East, taking centre stage instead of Great Britain; but updated to contain all the lands discovered since that empire crumbled, filling in those fabled ‘nagû’ with the locations they may have been supposed to represent.

So the arduous task was set. But after countless hours spent poring over maps, drawing, redrawing, tearing up and starting again, ironically only fragments of this sought after map remain. One piece from this fabrication sits alongside a section reconstructed by the Serbian artists Dušan Savić and Marida Avramović, yet only hints at the identity of the whole.

The rest of the world is blank, waiting to be colonised once more by the imagination. The act of depicting the world should be a collaborative event, and not a selfish burden of my own. The world is an open invitation to explore and this map offers you the same, either inside your head or committed to paper.

For the invaluable help given to me deciphering the original Babylonian artefact I must thank Dr Irving Finkle of the British Museum, and apologise for any mistakes I have made in these descriptions. This is just another story, muddied in the act of retelling.

So the arduous task was set. But after countless hours spent poring over maps, drawing, redrawing, tearing up and starting again, ironically only fragments of this sought after map remain. One piece from this fabrication sits alongside a section reconstructed by the Serbian artists Dušan Savić and Marida Avramović, yet only hints at the identity of the whole.

The rest of the world is blank, waiting to be colonised once more by the imagination. The act of depicting the world should be a collaborative event, and not a selfish burden of my own. The world is an open invitation to explore and this map offers you the same, either inside your head or committed to paper.

For the invaluable help given to me deciphering the original Babylonian artefact I must thank Dr Irving Finkle of the British Museum, and apologise for any mistakes I have made in these descriptions. This is just another story, muddied in the act of retelling.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed